About Francis Bacon

“I have often tried to talk about painting but writing or talking about it is only an approximation, as painting is its own language and is not translatable into words.”

Francis Bacon

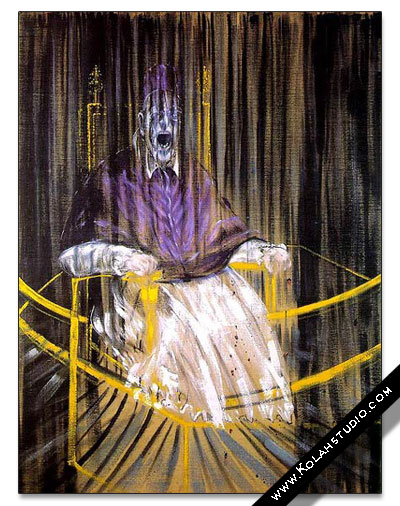

Bacon painted on the reverse side of primed canvases. This was his favourite surface because of its dryness and the fact that it does not completely absorb the colour. Although he used pastels or acrylic paints for the ground, which is generally plain and flat, the figures are executed in oil colour, which dries far more slowly. This allows for greater flexibility, by making it easier to change things as the work progresses. Bacon applied the paint with a variety of brushes, and sometimes with his bare hands, or with such other brush substitutes as rags, sponges, combs, and even cashmere pullovers – whatever seemed to recommend itself at the time. ‘I use anything’, he told David Sylvester: ‘I use scrubbing brushes and sweeping brushes and any of those things I think painters have used’. Parts of some pictures are painted with a spray can; in other cases, the colour is literally thrown on at random, or mixed with bits of pullover fluff and dust from the studio floor, and sometimes whole of the canvass are left bare. Here and there one also notices little circles of colour made with the caps of a paint tube or the lids of a discarded tin can; in the 1972 triptych Three Studies of figures on Beds, Bacon even used a dustbin lid to trace the swirling lines that surround two figures wrestling on a bed.

Bacon was concerned with two things here. First, the continual interruption of the painting process served to sustain a tension that might otherwise have been lost. And second, the unorthodox method of working the paint made the picture itself more interesting, by varying the texture and introducing an extra element of visual conflict. When asked by Sylvester why he used so many different tools, Bacon said: ‘I use these other practices just to disrupt it. Half my painting activity is disrupting what I can do with ease.’

For several reasons, he preferred his paintings to be hung under glass. As well as protecting the surface and establishing a distance between the picture and the viewer, the glass helped Bacon himself to achieve a sense of detachment that prevented him from revising or destroying his own work. Above all, however, it had the effect of reducing the volatility of the surface structure and endowing the work with a stronger feeling of coherence and finality. ‘I feel that, because I use no varnishes or anything of that kind, and because of the very flat way I paint, the glass helps to unify the picture. I also like the distance between what has been done and the onlooker that the glass creates; I like the removal of the object as far as possible’. (Sylvester, 1987, p. 87)

Bacon was a painter and nothing else. He produced few drawings, water-colours or gouaches, and no prints. He did not believe in making preparatory sketches, fearing that they would detract from the immediacy of the painting process. Instead he relied almost entirely on spontaneous inspiration. When he began to work on a picture, he did not really wish to know what the outcome would be. The tension and excitement of painting came from uncertainty: Bacon wanted the picture to take him by surprise.

Figure and ground

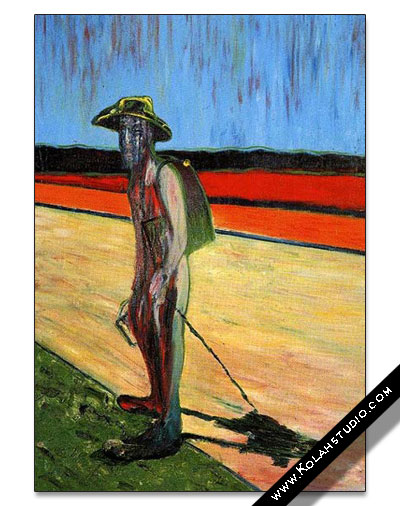

Perhaps ‘the’ distinguishing feature of Bacon’s painting style is the disjunction, found almost throughout his oeuvre, of figure and ground. His human subjects are entirely dissociated from their surroundings, which are no more than a kind of stage set or backdrop, lacking all sense of solidity or intrinsic relationship to the actors. There is a fixed and fundamental sense of remoteness between people and the world they inhabit. Bacon’s realism consists in expressing this feeling of strangeness or forgiveness via the means he deemed suitable for the purpose.

Except in the Van Gogh series, Bacon’s foregrounds and backgrounds are featureless, neutral and static, where his figures are in a state of permanent agitation; their bodies, bursting with nervous energy, are racked by continual spasms of tension and pain. The ground exhibits an almost surgical cleanliness, sullied only, if at all, by the activities – or the sheer presence – of human beings.