Magic

Mithraic mystical cosmology – the idea that Mithras, the unconquerable `sun behind the sun’, ruled the world through the medium of the zodiacal signs through which he passed – was at one time a serious rival to Christianity. It was essentially a magical interpretation of the world; and it influenced, and was influenced by, both Gnosticism and Theurgy. The Mithraic conception of man evolving through stages of spiritual development symbolized by the various planets exerted a permanent influence upon Western magic.

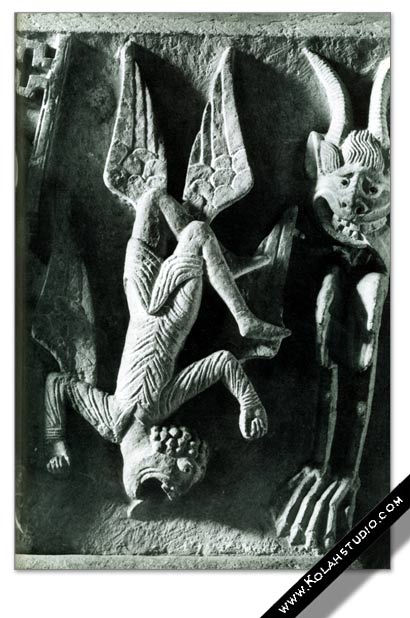

Simon Magus was the founder of one of the earliest Gnostic sects. We know little of his real teachings, for we can see him only through the eyes of his opponents, the orthodox Christians. They regarded him as a black magician, who, with the assistance of the legions of hell, performed diabolic miracles such as flying through the air. Eventually, according to the Christian legend, the white magic of Peter, the apostle of Christ, overcame the black magic of Simon; the demons who supported him during his flights were overcome and he fell to his death.

Fall of Simon Magus, detail of capital by Gislebertus, Autun cathedral, 12th c.

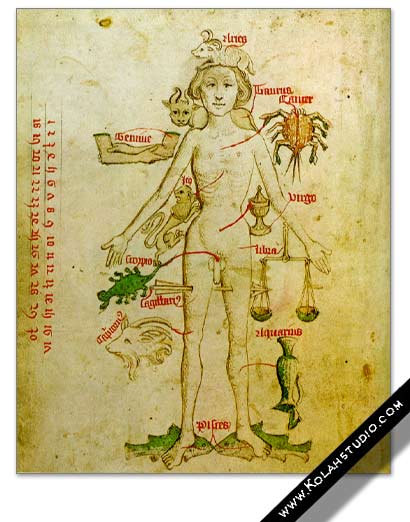

Astrology, which had been preserved by Arab scholars, reached Western Europe in the twelfth century, and did much to revive the magical traditions of the Thcurgists of antiquity. As planetary spirits, the pagan gods entered the Christian world-picture. With astrology came the Theurgists’ doctrine of correspondences. This illustration shows the supposed correspondences between the zodiacal signs and the parts of the human body, but there were thousands of other correspondences derived from astrology. The planetary spirit of Venus, for example, corresponds with roses, pigeons, the number seven and an almost infinite number of other material objects.

Zodiacal man, miniature from Guild book of the barber Surgeons of York, 15th c.

A belief in devils is as old as mankind. Always they have been feared, but sometimes, as here, they have been portrayed as figures of fun – laughter helps to keep fear at bay. ])evils, of course, have no objective existence, but they arc psychic realities; and those who have experienced these same psychic realities when they have taken on a form perceptible to the senses-usually through the use of drugs, drink or other chemicals which `loose the girders of the soul’

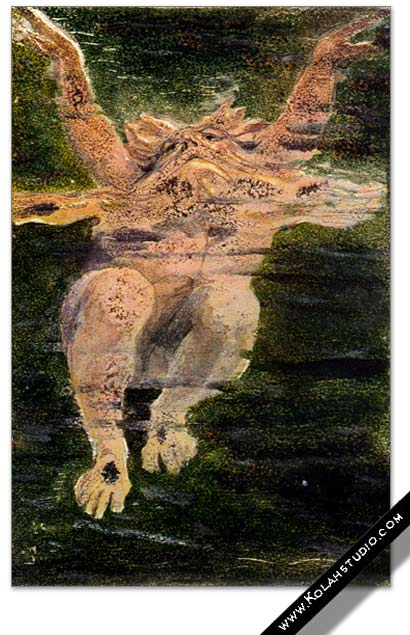

Magicians have always averred that some artists have the power of directly apprehending the realities of the astral world – of entering into the consciousness that lies ‘above’ mcrc physical existence. While this occult terminology may repel many, few would disagree with it if rephrased in psychological terms: `many artists have the ability to bring up images from the deepest levels of the unconscious’.

Some magicians have always used drugs as a technique Of Consciousness expansion. III recent times such drugs have included hashish, anhalonium and LSD. Less well known but equally potent preparations were used by the magicians and witches of medieval Europe. This young witch – ready for both love and the astral delights of the Sabbath – has coated herself with an ointment containing such herbs as henbane, belladonna and hemlock. All these are hallucinogens, drugs that Will `loosen the girders of the soul’.

Alchemy has always had a close relationship with ritual magic. Magicians, indeed, have regarded it only as a branch of magic, arguing that he who prepares the Philosophers’ Stone is merely purifying base matter in the same way that he who conducts a ritual initiation is purifying the candidate.

Urizen struggling with the waters of materialism, by William Blake, from The Book of Urizen 1794

From ancient Rome to modern London, from Proclus to Yeats, the philosophy of most magicians has beer) tinged with a dualism which has seen spirit as `good’, matter as `evil’, man as an immortal spirit trapped in the world of the flesh. William Blake, deeply influenced by the magical tradition as it was reflected in the writings of Behmenists and Swedenborgians, struggled against this belief but never quite overcame it. He gave it superb expression in his illustration of Urizen (who, on one level, represents the archetypal human spirit) struggling against the waters of materialism -`the atoms of Democritus and Newton’s particles of light’.

Resources

Book:

Magic, The western Tradition – Thames and Hudson